Altered Immune Cells in Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Patients Cause Reduced Immune Capacity

Written by |

In a new study entitled “Polymorphonuclear Cell Functional Impairment in Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Patients: Preliminary Data” researchers investigated how polymorphonuclear cells — important players of the innate immune system — are altered in multiple sclerosis patients. The study was published in the journal PLOS One.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system due to the immune system attacking myelin, a component of nerve fibers, resulting in a wide range of neurological symptoms affecting visual, motor and sensory capabilities. Researchers are increasingly recognizing the link between the central nervous system (CNS) and the immune system, leading to MS patients exhibiting a higher risk of developing immunodepression (a deficiency in one or more components of the immune system) and bacterial infections — conditions that are among the leading causes of death in MS patients.

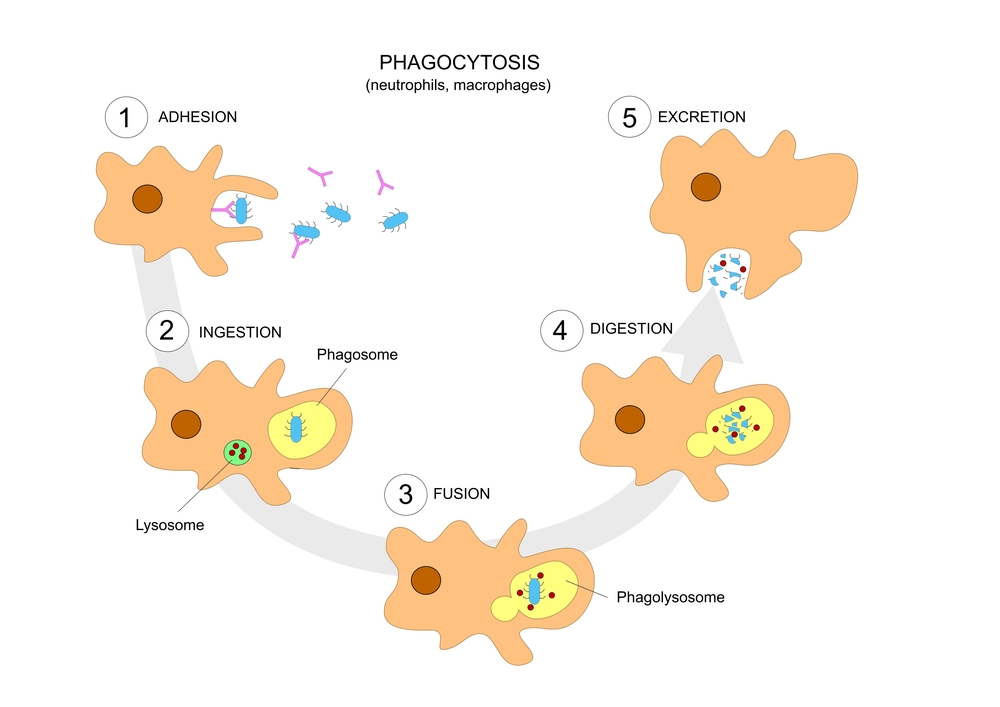

A key component of the innate immune system are polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), which are responsible for phagocytosis (ingestion or engulfment other cells or particles) and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), key steps in combating infections. Notably, MS patients were reported to exhibit decreased levels of PMNs with altered functions, which may cause the increase in infection risk.

In this new research, the authors investigated how the functional capacities of PMNs are altered in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), characterized by clearly defined attacks of worsening neurologic function which are then followed by periods of partial or complete recovery periods (called remissions) when compared to PMNs from healthy individuals. Specifically, they measured the ability of PMNs retrieved from MS patients to secrete cytokines, produce ROS, and regulate cell death when infected with a bacteria, Klebsiella pneumonia and a fungus, Candida albicans.

The team found that while PMNs from healthy control individuals and untreated RRMS patients exhibit a similar intracellular killing activity against both Klebsiella pneumoniae and Candida albicans, PMNs from RRMS patients that received MS treatment (drugs that modulate or suppress the activity of the immune system) had a significant decrease in their ability to actively kill the intracellular organisms. To determine if indeed the treatment was the underlying cause of the decline in PMNs killing activity, the researchers pre-treated healthy patients’ PMNs with an immunosuppressive drug. They observed that the drug-pretreated healthy subjects’ PMNs also had reduced killing activity — significantly lower then the activity observed without the pre-treatment.

No other alterations, production of reactive oxygen species and cell death regulation were observed between the different subjects analyzed, which included healthy controls as well as untreated and treated RRMS patients.

Therefore, although the team recognizes some limitations to their study, they suggest that the higher incidence of microbial infections in treated RRMS patients is due to an impairment of PMN activity. Additionally, studies are mandatory to further understand the link between MS, the innate immune system and therapy so that patients can be managed and receive the appropriated treatments according to their risk of infection.