MS May Be Triggered by the Death of Brain Cells

Written by |

Researchers are proposing for a first time that multiple sclerosis (MS) is triggered by the death of a specific cell population within the central nervous system called oligodendrocytes. The study, titled “Oligodendrocyte death results in immune-mediated CNS demyelination,” was published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

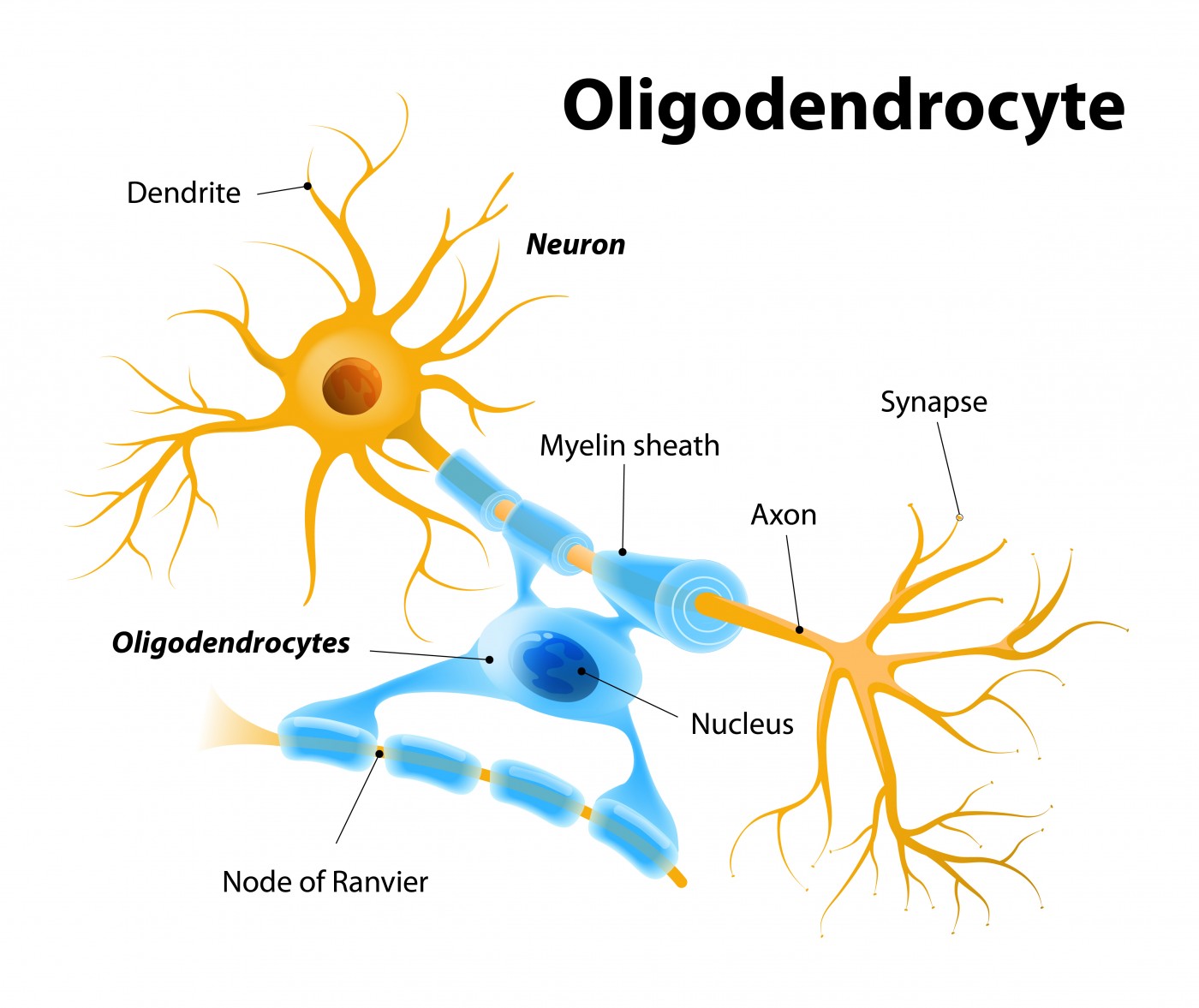

Oligodendrocytes, together with Schwann cells, are the central nervous system (CNS) cells responsible for the formation of myelin — an insulating layer that forms around nerves, including those in the brain and spinal cord, and which allows electrical impulses to be transmitted quickly and efficiently along the nerve cells.

The etiology of the autoimmune attack against myelin that characterizes MS is largely unknown. A team of scientists at the University of Chicago and Northwestern Medicine investigated whether oligodendrocyte death could cause this autoimmune response. The researchers generated a genetically engineered novel mouse model that allowed them to specifically target oligodendrocytes and induce their ablation.

The team observed that death of oligodendrocytes induced MS-like symptoms, impairing the mice’s ability to walk. Although the CNS was capable of regenerating the myelin-producing cells and the mice began walking again, the phenotype was finite, and within six months, the mice again developed MS-like symptoms.

Maria Traka, PhD, research associate professor in neurology at Chicago and study co-author, said in a press release, “To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that oligodendrocyte death can trigger myelin autoimmunity, initiating inflammation and tissue damage in the central nervous system during MS.”

The research team hypothesized that MS could actually be developing within years after a first injury in the brain induces oligodendrocyte death.

Brian Popko, PhD, Jack Miller Professor of Neurological Disorders at the University of Chicago and study co-lead author added, “Although this was a study in mice, we’ve shown for the first time one possible mechanism that can trigger MS — the death of the cells responsible for generating myelin can lead to the activation of an autoimmune response against myelin. Protecting these cells in susceptible individuals might help delay or prevent MS.”

Investigating a possible therapeutics, researchers tested the administration of nanoparticles in mice in order to induce tolerance against the myelin antigen, and observed that this strategy prevented the development of progressive MS. This technology, developed in Dr. Stephen Miller’s laboratory and recently licensed to Cour Pharmaceutical Development Company, is being further developed for testing in human autoimmune disease clinical trials.

Dr. Popko said, “We’re encouraged that the nanoparticles could stop disease progression in a model of chronic MS as efficiently as it can in progressive-remitting models of MS.”

“It’s likely that therapeutic strategies that intervene early in the disease process will have greater impact,” added Dr. Miller, PhD, Judy Gugenheim Research Professor of Microbiology-Immunology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

These new findings challenge the current theory that MS is triggered by external CNS stimuli. Scientists here suggest that MS begins from the inside out, with damage to oligodendrocytes inducing myelin to fall apart, and their components, in turn, trigger an autoimmune response. The team is already focusing on the next challenges. As Dr. Popko concluded, “It will be exciting to determine the nature of this process in humans — its precise role in MS and whether therapies to prevent it are effective.”