New Pre-HSCT Treatment May Make Stem Cell Transplants a Safer Option for MS Patients

Written by |

Scientists at Stanford University School of Medicine have developed a method for stem cell transplants that may do away with the need for prior systematic treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy. If successful, stem cell transplants could be an option for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), an option now limited by the risk of severe toxicity triggered by the chemotherapy.

The study, “Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in immunocompetent hosts without radiation or chemotherapy,” was the cover story of the latest issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine. The method has been successfully tested in mice, but if proven safe and effective in humans, it could truly revolutionize MS treatment, as well as the treatment of a host of other conditions.

“If it works in humans like it did in mice, we would expect that the risk of death from blood stem cell transplant would drop from 20 percent to effectively zero,” the study’s senior author, Dr. Judith Shizuru, MD, PhD, and a professor of medicine at Stanford, said in a news release.

While blood, or hematopoietic stem cell transplants, known as HSCT, have been available for MS patients for some time, health authorities in many countries — including the U.S. and EU — have not yet approved such treatments for MS. Lately, studies have supported the idea of stem cells being used for MS and a recent clinical trial found the method successful in 23 out of 24 patients.

The final patient is, however, what prevents the treatment from becoming a standard treatment for all MS patients. That person died of damage caused by chemotherapy.

Aggressive chemotherapy, needed to wipe out all the old bone marrow cells, is not easy for the body to endure. In addition to killing the old stem cells, it kills a host of other cells and can cause liver damage, destroy the ability to have children, and lead to irreparable brain damage. On a longer time scale, cancer is one of the most common side effects of chemotherapy. (Of note, the Canadian trial used a highly potent chemotherapy regimen, chosen because of its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. But the doses were higher than those used in most HSCT clinics now making this therapy available to MS patients.)

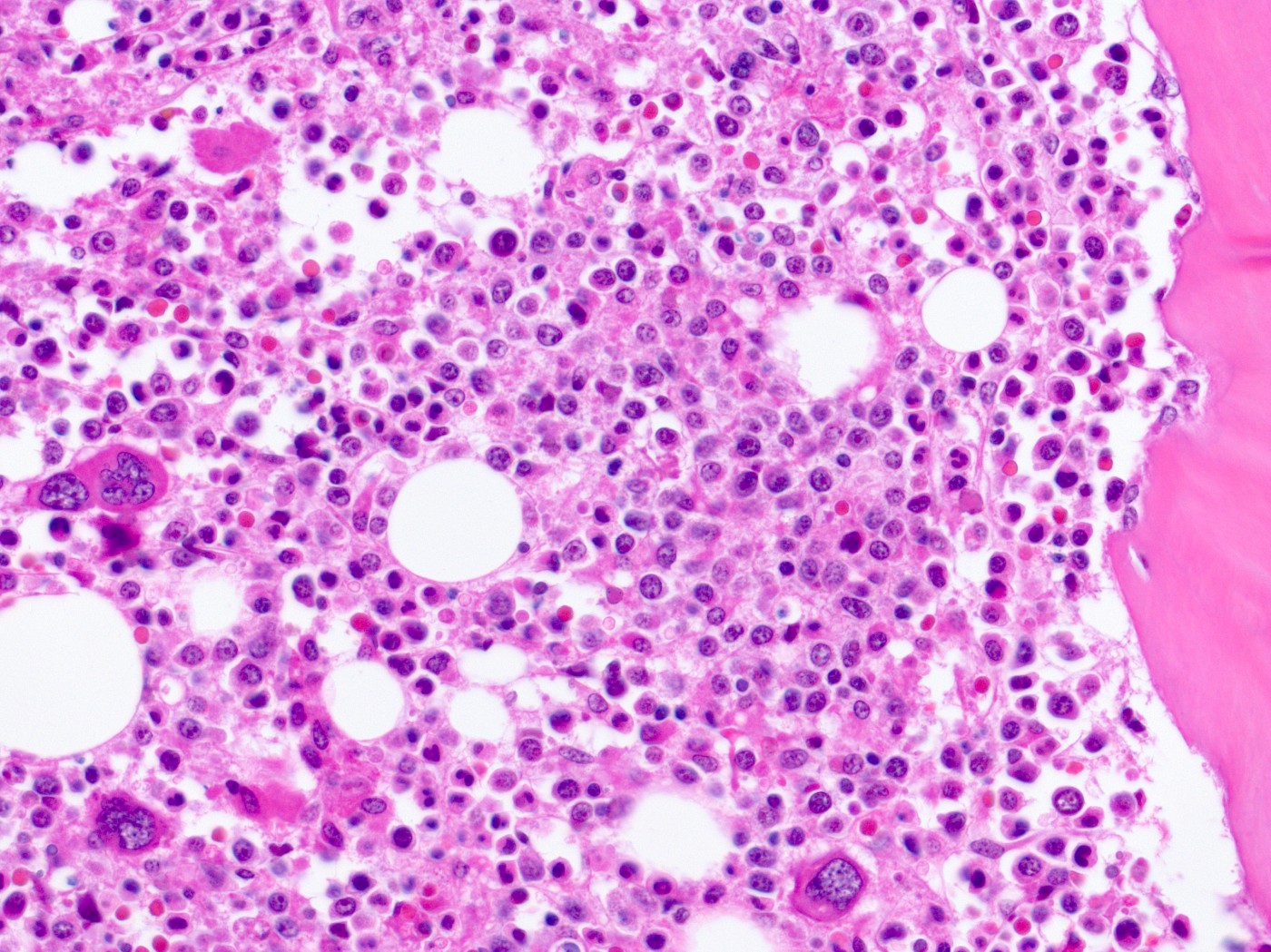

Instead of killing all dividing cells, like chemotherapy does, Stanford researchers developed a much more precise method to get rid of old stem cells. A combination of two antibodies — one targeting a surface protein called c-Kit on blood stem cells, and another that blocks a molecule called CD47 — allowed immune cells called macrophages to destroy cells covered with anti c-Kit antibodies.

In mice, the combination rapidly cleared old stem cells, allowing for the successful transplant of new stem cells with very little side effects.

In addition to this safer method to clear the way for new stem cells, researchers also improved the transplant itself. Cells taken from the bone marrow — the ones that are used for stem cell transplants — are effectively a mix of stem cells and various immune cells from the donor. These old immune cells contribute to what is known as graft-versus-host disease, with the old cell system attacking the tissues of their new host. The researchers “purified” the donor tissue so that it contained only blood stem cells.

Most MS stem cell treatments use so-called autologous transplants, taking out the patient’s own stem cells before killing the immune system with chemotherapy. Today, successful autologous stem cell transplants may put off symptoms and disease progression for years, but many patients do relapse after transplants, and lingering immune cells in a transplant derived from the patient’s own bone marrow likely contribute to that.

“If and when this is accomplished, it will be a whole new era in disease treatment and regenerative medicine,” said Dr. Irving Weissman, MD, a study co-author and professor of pathology and developmental biology at Stanford, who is also the director of the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, and director of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Stem Cell Research and Medicine.