People with MS Are Three to Six Times More Prone to Seizures Than Others, Study Reports

Written by |

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) are three to six times more likely to develop epilepsy than the general population, a study says.

Researchers believe the loss of myelin in certain neurons — a hallmark of MS — is what causes the seizures.

The study was published in the journal Neuroscience under the title “Chronic Demyelination-Induced Seizures.”

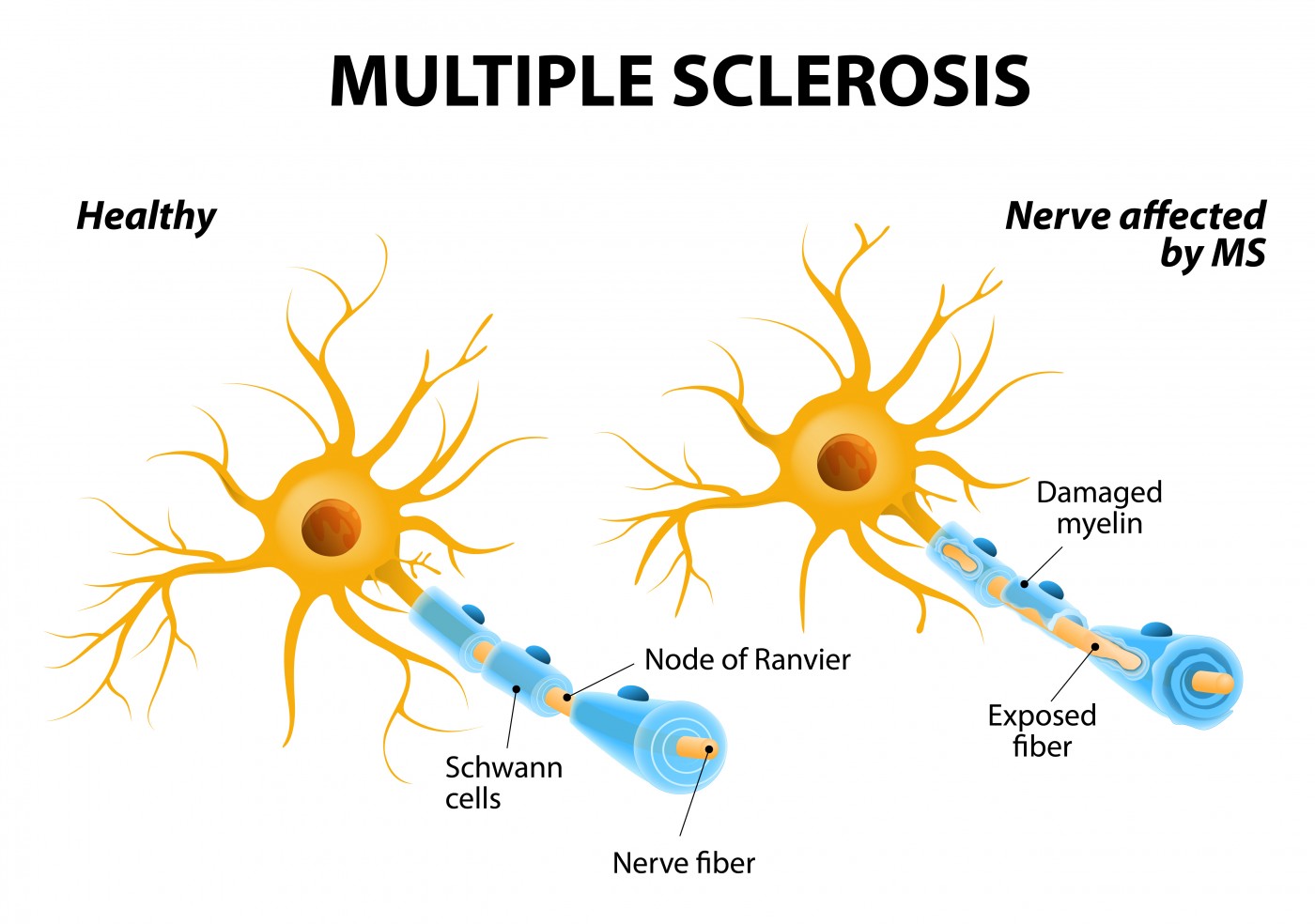

The myelin sheath is a coating that protects neurons. It is progressively lost in MS due to a malfunctioning immune system attacking and destroying it. Myelin degeneration destabilizes neuron function and ultimately leads to cell death, contributing to disease progression and disability in MS patients.

Neurons known as parvalbumin interneurons are responsible for preventing hyperactivity. In MS, these neurons lose their myelin protection, affecting their activity in the brain. Researchers believe this loss causes seizures.

“Demyelination causes damage to axons and neuronal loss — specifically, parvalbumin interneurons are lost in mice, hyperactivity is no longer down but up, and this could be a cause of seizures,” Seema Tiwari-Woodruff, the study’s senior author, said in a news release. “It’s very likely this is what is occurring in those patients with MS who are experiencing seizures.”

Researchers studied myelin loss by feeding mice with food containing cuprizone, a compound that damages myelin-producing cells called oligodendrocytes. After nine weeks of the diet, most mice started to have seizures.

“Without myelin, axons are vulnerable,” Tiwari-Woodruff said. “They develop blebs – ball-like structures that hinder transport of important proteins and conduction of electrical signals. In some instances, significant [neuronal] damage can lead to neuronal loss. In both MS and our mouse model, parvalbumin interneurons are more vulnerable and likely to die. This causes the inhibition to be removed and induce seizures.” This means that “neuronal survival may be directly tied to the trophic support provided by myelin.”

When the researchers stopped feeding cuprizone to mice, oligodendrocytes started producing myelin again, remyelinating the intact neurons. Whether remyelination decreases seizures remains unknown.

“Does remyelination affect seizure activity? Could we accelerate the remyelination with drugs? Can we thus provide some relief for MS patients? We are interested in addressing these questions,” Tiwari-Woodruff said.

The team plans to continue studying the mechanisms linking MS and epilepsy. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society has given it a grant to compare brain tissue from deceased MS patients who had experienced seizures with brain tissue from deceased healthy individuals. The researchers also want to understand how similar MS in the cuprizone mouse model is to MS in patients.

“We want to know if these [human] tissues show what we are seeing in our mouse model,” Tiwari-Woodruff concluded. “Our preliminary data in postmortem tissue show considerable similarity between the two. We now have a mouse model with which we can work to test and suggest some therapeutic cures. When developed, such drugs, which would be aimed at reducing hyperactivity to reduce the incidence of seizures, could also be extended to epilepsy patients.”