Vitamin D Supplements at Preclinical Stage Prevented MS in Mice

Vitamin D, but not paricalcitol (a vitamin D analog), can be used as a preventive measure to control the severity of multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a new study of mice.

The study, “Preclinical therapy with vitamin D3 in experimental encephalomyelitis: Efficacy and comparison with paricalcitol,” was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

Many studies have investigated the benefits of vitamin D supplementation for MS, with mixed results.

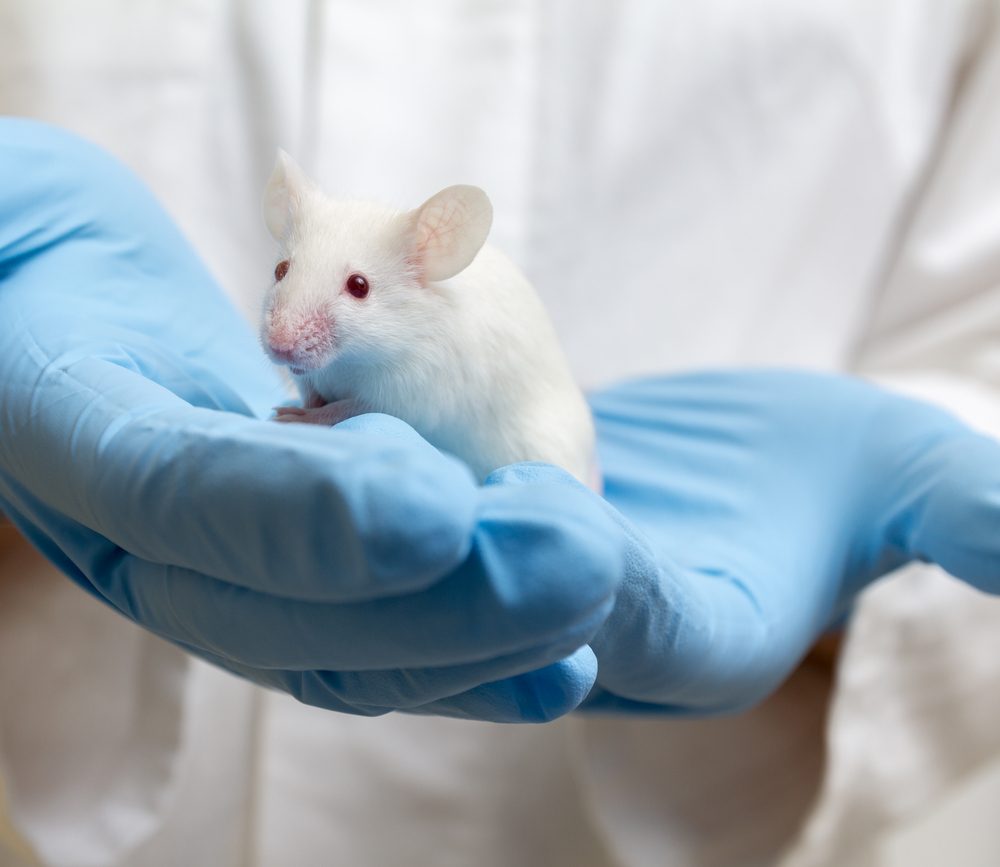

A team led by Alexandrina Sartori, PhD, at São Paulo State University, Brazil, has been using experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of MS, to show that administration of vitamin D during the preclinical phase of the disease could be prophylactic (preventive).

The preclinical phase of a disease is the period of time when symptoms are not yet apparent, but the disease is biologically present.

“We recently observed that an early intervention with [vitamin D], delivered 24 hours after experimental encephalomyelitis induction, prevented neurodegeneration,” the researchers wrote.

The team wanted to know what happens when vitamin D is given later during the preclinical phase of the disease. More specifically, vitamin D was given to EAE mice every other day starting seven days after the induction of experimental encephalomyelitis, when the autoimmune response is already established.

Vitamin D promotes normal calcium absorption in the intestine, but vitamin D supplements can cause hypercalcemia; that is, they can raise calcium levels in the blood above normal.

“The fact that [vitamin D] causes hypercalcemia cannot be neglected because of its pathophysiological consequences,” the researchers wrote.

Therefore, they compared the effects of vitamin D with those of paricalcitol — a compound that is structurally similar to vitamin D, but does not result in higher-than-normal calcium levels in the blood.

Using EAE mice, the researchers found that vitamin D, but not paricalcitol, reduced the clinical signs of disease. However, as expected, vitamin D increased serum calcium levels compared with those in healthy, untreated mice.

Next, the researchers asked if vitamin D could reduce inflammation and demyelination — the loss of the protective myelin sheet surrounding nerve fibers and the hallmark of MS — in the central nervous system.

Indeed, microglia (specialized immune cells of the central nervous system) in vitamin D-treated mice expressed lower levels of MHC class II molecules compared with those in untreated or paricalcitol-treated groups.

MHC class II are molecules loaded with antigens, which are able to trigger an immune response, that are presented to immune cells such as T-cells. In MS, where T-cells turn against proteins in the central nervous system, fewer MHC class II molecules on the surface of antigen-presenting cells could mean T-cells can be tamed.

While all EAE mice showed signs of demyelination, those treated with vitamin D had a smaller extension of demyelination — about a 2.5-fold reduction compared with untreated or paricalcitol-treated mice.

Inflammation of the gut, where T-cells home before they migrate to the central nervous system, also was better controlled by vitamin D than by paricalcitol.

Further experiments in vitro showed that vitamin D, but not paricalcitol, reduced the levels of certain pro-inflammatory signaling molecules called cytokines.

Altogether, the findings suggest that vitamin D, but not paricalcitol, “has the potential to be used as a preventive therapy to control MS severity,” the researchers wrote.

“This failure [of paricalcitol] was unexpected considering that previous publications attested protective ability by other vitamin D analogs,” they added. “This finding points to the need to thoroughly investigate and compare the numerous available vitamin D analogs concerning their immunomodulatory potential.”

Concerning the timing of vitamin D administration, “our data highly suggest that there is a window of opportunity for [vitamin D] treatment in EAE,” the researchers wrote. “Our results indicate that [vitamin D] efficacy still takes place if therapy is postponed to the preclinical disease stage, even though its effect is less stringent as compared with more precocious or even prophylactic measures as we and other authors have previously demonstrated.”