Stem Cell Transplant for MS Eases Fatigue, Improves Life Quality

Reduced disability found in patients up to 2 years post-aHSCT

Written by |

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) — commonly called stem cell therapy — lessens fatigue and improves quality of life in people with highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a small study in Lithuania.

These gains in the physical and social domains of quality of life were linked to a reduction in disability levels for up to two years after transplant in this study. That suggests that clinical improvements from aHSCT may drive boosts in life quality for MS patients.

The findings address a gap in knowledge about patient perspectives on the success of a stem cell transplant beyond clinical measures of MS disease severity, the researchers noted.

The study, “Impact of autologous HSCT on the quality of life and fatigue in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis,” was published in Scientific Reports.

Stem cell transplant for MS

aHSCT is an intensive, experimental approach that is expected to stop the abnormal immune attacks and inflammation that drive neurodegeneration in MS. It works, essentially, by resetting a patient’s immune system.

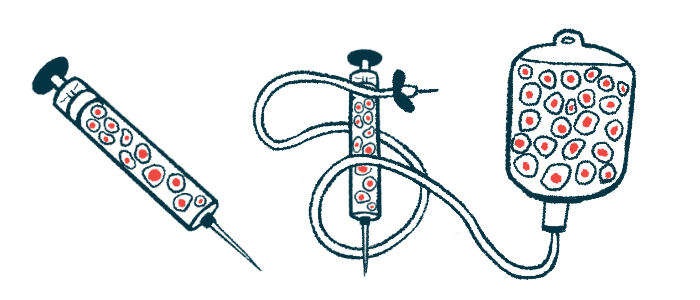

The treatment involves collecting a patient’s blood stem cells — a set of cells with the capacity to produce virtually any other type of blood cell — from the bone marrow and then wiping out the person’s immune system using chemotherapy and/or radiation.

The stem cells are then infused back to the patient, where they will repopulate the immune system with healthy cells.

Such stem cell therapy is not approved in the U.S. But the procedure is backed by the National MS Society for patients with very aggressive relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) who have responded poorly to other disease-modifying treatments.

A growing body of data suggests that aHSCT is effective for these MS patients, with studies indicating that a stem cell transplant can prevent relapses and disability progression. A review study covering 4,831 MS patients found that in the five years after transplant, 73% of patients were alive and without disability progression. Moreover, 81% were relapse-free.

Aside from these measures of disease progression, however, little is known about the potential effects of aHSCT on quality of life. There also are scant data on fatigue, anxiety, and depression — common MS symptoms that negatively affect quality of life.

“Assessing the impact of these interventions on [quality of life] and fatigue is important because it highlights the patient’s perspective on the overall effect of the treatment,” the researchers wrote.

To address this knowledge gap, a team of researchers in Lithuania and Switzerland examined the impact of aHSCT on fatigue, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in 18 adults with highly active relapsing MS. Their study involved 15 women and three men who did not respond to the second line of MS treatment.

Highly active relapsing MS patients were defined as those who experienced at least two relapses and had disability progression of at least two points according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) in the prior year.

Before the transplant, patients’ mean age was 35.2; they had been living with the disease for a mean of 8.6 years. Their median scores on the EDSS were 6, reflecting disability severe enough to require assistance to walk and work.

All patients underwent aHSCT at the Vilnius Multiple Sclerosis Center, in Lithuania. Disease progression, quality of life, fatigue, and mood symptoms were evaluated before aHSCT and at three time points afterward: three months, one year, and two years later.

Results showed that the number of relapses per year dropped from 2.7 before transplant to 0.17 in the first year, and 0.11 in the second year, reflecting a decline in relapses after the procedure.

Most patients (77.8%) also showed a reduction in disability severity, as reflected by a drop in EDSS scores, at three months after transplant. After that point, the scores generally remained stable. Sustained disability reduction was observed in 66.7% of patients at one year, and 61.1% at two years.

The remaining patients — about 22%, or just less than one-quarter — did not experience a change in disability after transplant.

Improvements in quality of life

The 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) was administered to evaluate quality of life. aHSCT resulted in improvements in all SF-36 domains at three months, and these gains were sustained for two years.

Notably, such differences reached statistical significance for the physical functioning, vitality, and pain domains.

“The lack of significance in other domains, like general health, role limitation because of physical and emotional problems, and social functioning, may be related to a relatively small sample size,” the researchers wrote.

Also, a trend of reduced fatigue was observed at three months, with significant drops being detected at one year and sustained until two years.

Prior to the transplant, half of the patients had moderate depression and seven (38.9%) had severe depression, whereas 72.2% had moderate anxiety and one patient (5.6%) had severe anxiety. Anxiety and depression scores were generally unchanged after treatment.

In the subset of patients who did not experience a lessening of disability after aHSCT, physical function, vitality, fatigue, and anxiety also were unchanged. However, pain and depression were significantly eased in these patients a year after the transplant.

Further analyses showed that lower EDSS scores, reflecting less disability, were significantly associated with quality of life improvements in physical and social functioning, as well as reductions in physical role limitations, at two years.

These results suggest that “in patients with highly active relapsing MS, disability regression is the main value that has a positive impact on [health-related quality of life] outcomes, especially physical and social outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, “aHSCT improved quality of life and reduced symptoms of fatigue in patients with highly active relapsing MS,” they added, noting that the low number of participants hinders the generalization of the findings to the larger MS population.

“Further research is needed to replicate these findings,” the team concluded.