Most MS patients stay relapse-free 6 years after stem cell transplant

Gains may result in patients being able to resume employment

Written by |

About 4 in 5 people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) who receive a stem cell transplant remain free of relapses for at least six years, and this may translate into being able to get back to work, a small study from Norway suggests.

The study, “Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: Long-term follow-up data from Norway,” was published as a short report in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal.

RRMS is the most common type of multiple sclerosis (MS), accounting for about 90% of all newly diagnosed cases. People with this form of the disease go through periods where they suddenly have new or worsening symptoms, called relapses or flare-ups, followed by periods of remission where symptoms ease or go away.

Generally, patients who have more frequent relapses and poorer symptom recovery during remissions accumulate disability faster, which can be challenging for daily living and work. Even with workplace adjustments, they may need to reduce the number of hours they work and some may no longer be able to keep a job.

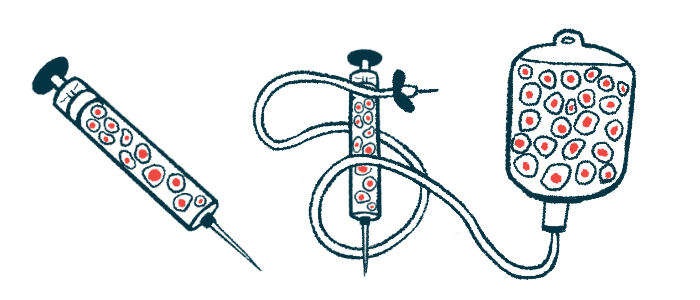

Accumulating evidence suggests autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), or stem cell transplant, may help with relapsing forms of MS, especially when the disease is more active or the patient doesn’t respond to available MS treatments.

The procedure is designed to reset the immune system and tame the excess inflammation that drives MS, helping patients enter into sustained periods of remission.

Long-term benefits of stem cell transplant

A stem cell transplant involves collecting a patient’s own hematopoietic (or blood-forming) stem cells from the bloodstream or bone marrow. A chemotherapy and/or radiation regimen is then given to wipe out the immune system and the stem cells are infused back to produce an entirely new immune system. In theory, this produces immune cells that aren’t primed to attack the nervous system, helping to reduce the inflammation that drives MS for prolonged periods.

Here, researchers in Norway looked at the long-term benefits of this procedure in 29 adults, mean age 31, who’d had at least two relapses the year before receiving an autologous HSCT despite being on disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). Most patients had used two to four DMTs.

Over a mean of 70 months (almost six years), about two-thirds of the patients (69%) maintained a status called no evidence of disease activity (NEDA-3), meaning they had no relapses, no disability worsening, and no signs of new disease activity on MRI scans.

Among those who saw evidence of disease activity, the most common were new areas of damage on MRI scans, as observed in 21% of patients. Relapses were seen in 17% and confirmed disability progression in 10%. In general, the patients with disease activity had significantly higher disability levels before the transplant.

While 10% had disability progression, as determined by a sustained increase in Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores, 38% had disability improvements, meaning their EDSS scores decreased. The remaining had stable scores. At five years, the median EDSS score had dropped by 0.4 points compared with before the transplant.

The benefits were observed despite the use of a non-myeloablative regimen, wherein a patient receives a less aggressive course of chemotherapy and/or radiation to suppress the immune system enough to allow the new stem cells to settle in the bone marrow.

“Our findings show that non-myeloablative HSCT represents a therapeutic alternative with similar or better response with regard to disease activity,” wrote the researchers, who also observed how employment status changed after the transplant. Before the autologous HSCT, only one of the 29 participants (3%) worked full-time, which grew to 10 (33%) after two years and 15 (52%) after five years. Five (17%) patients had full-time disability benefits before the transplant, which increased to 10 (35%) five years after it. According to the researchers, this increase reflected “the same magnitude of patients not achieving NEDA.”

Over the follow-up, 17% of patients developed an autoimmune thyroid disease, and 62% had ovarian failure. Despite that, 17% had children, with one of them receiving a transplant of ovarian tissue after the transplant.

“The positive and lasting results regarding disease activity and work participation raise the question whether more MS patients should be treated with HSCT rather than modern DMTs,” the researchers wrote.