Genetically Engineered Cells Have Potential to Restore Neuron’s Myelin Sheath, Study Shows

Written by |

Genetically modified human umbilical cord blood cells can help nerve cells recover the myelin layer necessary for normal functioning, researchers found in a preclinical study.

This finding may support the development of cell-based therapeutic approaches to help patients with spinal cord injuries or demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS).

The study, “Influence of Genetically Modified Human Umbilical Cord Blood Mononuclear Cells on the Expression of Schwann Cell Molecular Determinants in Spinal Cord Injury,” was published in the journal Stem Cells International.

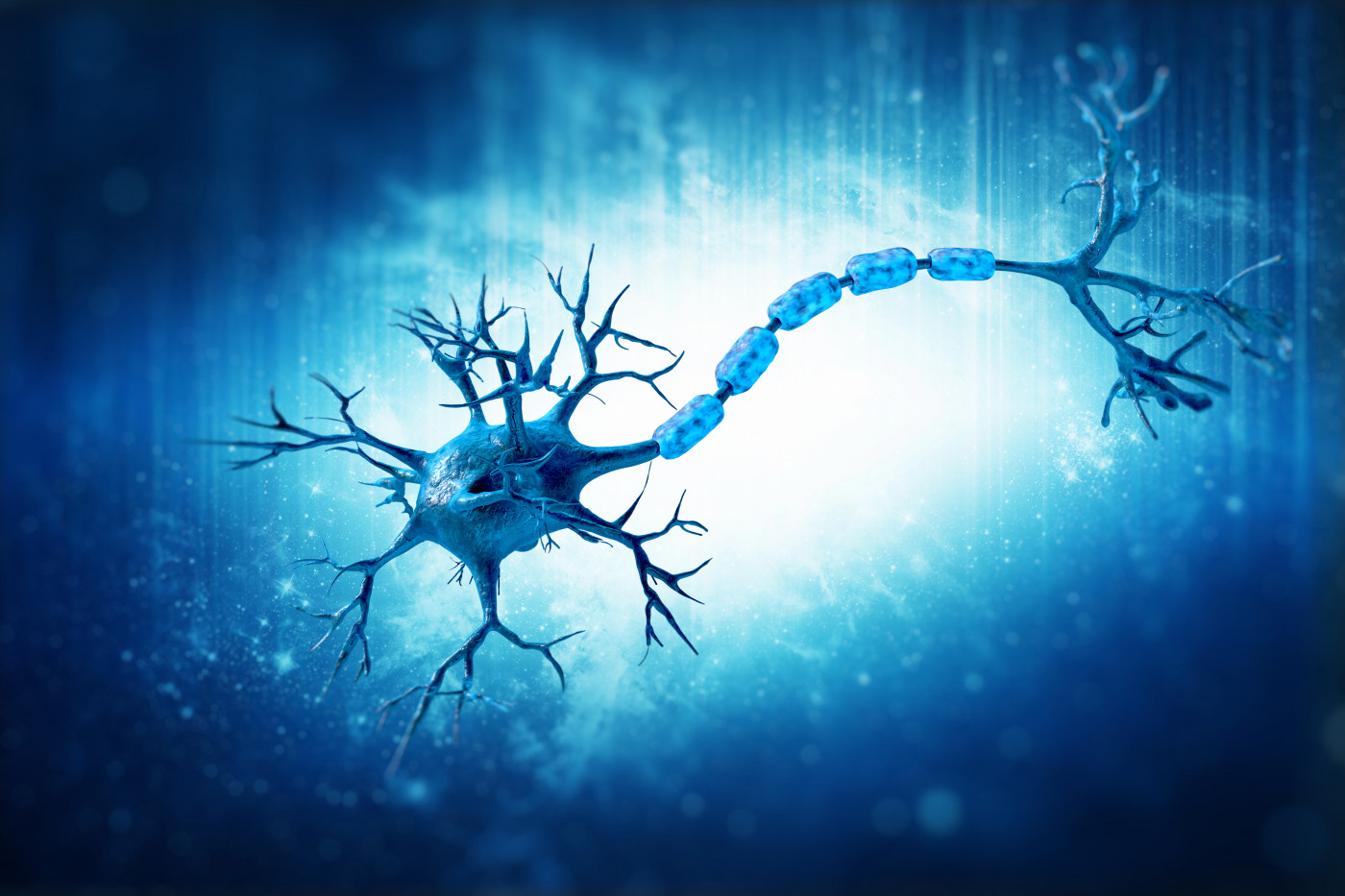

Myelin is an important structural component of neurons, or nerve cells. It not only protects the cells from damage, but it is also essential for the transmission of the electrical pulses neurons use to communicate.

Two types of cells are responsible for producing myelin — Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system, and oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system. These cells respond to a class of signaling molecules called neurotrophic factors, or NTFs, which promote the proliferation and migration of Schwann cells, and increase myelin production.

Previous studies have shown that umbilical cord blood cells may help restore immune system balance at the site of nerve cell damage, and repair the myelin sheath.

With this in mind, a team led by researchers at Kazan Federal University in Russia decided to evaluate the combined potential of umbilical cord blood cells with NTFs. The team genetically engineered these cells to produce two specific types of neuroprotective NTFs — glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factors and vascular endothelial growth factors — enhancing their therapeutic potential.

“These genes, or, more precisely, the proteins coded by them, can protect neurons and have a supportive influence on them. Thus, umbilical cord blood cells serve as transporters of therapeutic genes and a sort of mini bio plants of recombinant biologically active proteins in injured areas,” Yana Mukhamedshina, PhD, MD, group head at Kazan University’s gene and cell technologies lab and co-author of the study, said in a press release.

To evaluate the impact of the engineered cells, researchers injected them in rat models of spinal cord injury. This triggered an increased amount of Schwann cells at the site of nerve cell damage, suggesting that the modified cells can increase the numbers of myelin-producing cells at a damage site.

Further studies are still required to clarify what protective mechanism is being triggered by the engineered cells — if they are supporting increased migration and proliferation of Schwann cells, or if they are promoting survival of nerve cells. Still, these results suggest that Schwann cells can migrate to an injured area and participate in myelin production, thus replacing the functions of oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system.