Stem cell therapy for multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease wherein misguided inflammatory attacks cause damage in the brain and spinal cord, driving symptoms such as fatigue, depression, muscle spasms, and difficulty regulating the bladder and bowels. Several strategies using stem cells, which are self-renewing cells in the human body, are being explored as potential treatments for MS.

What are stem cells?

Most cells in the adult body are fully mature and cannot grow into another cell type. For example, a liver cell cannot turn into a brain cell. Stem cells, on the other hand, are the precursors to mature cells in the body. They are capable of self-renewal and have the potential to grow into all other types of cells.

These unique cells play several key roles, including:

- early tissue development

- tissue repair and regeneration after damage or injury

- self-renewal for tissues with naturally rapid cell turnover

Stem cells are generally divided into two forms:

- pluripotent cells, which are able to develop into every cell type found within the human body and are critical for early development. Most naturally occurring pluripotent stem cells are embryonic, meaning they’re found in a developing fetus.

- multipotent cells, which can grow into some types of cells but not others and often play key roles in tissue regeneration and repair throughout life. Adult stem cells found in mature tissues are usually multipotent.

Different types of stem cells

There are several types of stem cells, each with distinct biological properties. The two main types that have been studied and used in people with MS include:

- hematopoietic stem cells, or HSCs, also known as blood stem cells, reside in the bone marrow and give rise to all blood cells, including oxygen-carrying red blood cells and white blood cells that make up the immune system.

- mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are found throughout the body, but often give rise to connective tissue cells like bone, cartilage, fat, and muscle cells. They also produce and release many signaling molecules that coordinate the activity of surrounding cells.

A few other stem cell types that have been investigated in the context of MS include:

- neural stem cells, which grow into nerve cells and other nervous system support cells. These could provide neuroprotection or neuroregenerative capabilities.

- embryonic stem cells, which are pluripotent cells found in embryos during prenatal development.

- induced pluripotent stem cells, which are made in the laboratory by “reverse engineering” mature cells, usually from the skin or blood, back into a pluripotent stem cell state. These are commonly used as a research tool.

The potential immunomodulatory, neuroprotective, and regenerative capabilities of these various stem cell types make them appealing for treating MS. However, interest in developing them for clinical use in MS has not been as strong as with HSCs and MSCs for various logistical, ethical, and safety-related reasons.

No stem cell therapy for MS has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, some stem cell-based therapies are currently in clinical trials for MS, and HSC transplants have already been cleared for use in certain blood disorders.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)

Because HSCs give rise to most immune cells, it’s thought that they may be able to help reset the faulty immune system that drives MS inflammation. As such, they are sometimes administered to MS patients via a one-time treatment called a hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

It is possible to do the transplant with cells collected from a donor (allogeneic transplant), but this is associated with a higher risk of complications. More often, the procedure is performed using a patient’s own stem cells, known as an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT). In the context of MS, other terms for aHSCT include stem cell therapy, stem cell transplant, bone marrow transplant, or blood stem cell transplant.

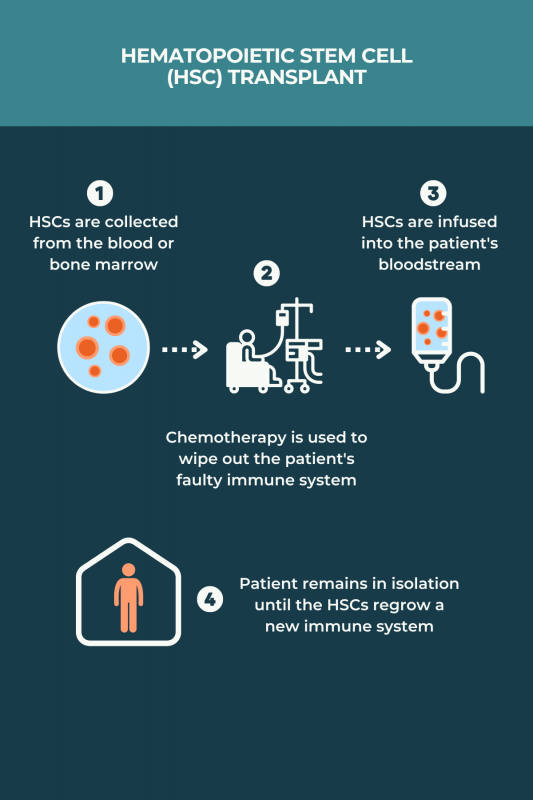

There is no standardized protocol for aHSCT in MS, and various regimens may be used. Typically, the process involves:

- medications to induce HSC production and stimulate their release, or mobilization, into the bloodstream

- collection of HSCs from the bloodstream after mobilization, or skipping mobilization and collecting the cells directly from the bone marrow

- treatments, usually chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, to completely wipe out the immune system and remove any faulty cells that are contributing to MS

- returning HSCs back to the patient via an infusion into the bloodstream to repopulate the immune system with healthy cells

The procedure typically involves spending several weeks in an isolation room at the hospital for close monitoring and infection prevention. Before going home, patients must wait for the HSCs to settle in the bone marrow and begin producing healthy immune cells.

Because the immune system typically takes about one year to fully rebuild, some precautions are recommended to prevent infections after discharge. The physical and mental health of the patient is closely monitored for two years after the transplant.

How effective is HSC therapy for MS?

While there’s no FDA approval for stem cells in MS treatment, the National MS Society has supported aHSCT as an effective option for select patients who:

- have relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS)

- are younger than 50

- were diagnosed with MS less than 10 years ago

- are unable to take highly effective disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) or continue to have high disease activity — relapses and/or MRI activity — despite using these medications

Studies have shown that for such patients, the MS immune system reset following aHSCT can reduce relapse rates, slow disability progression, ease symptoms, and improve quality of life. With appropriate patient selection, the success rate of stem cell therapy for MS is favorable. A 2022 analysis covering data from nearly 5,000 MS patients who underwent aHSCT showed that five years after the procedure:

- about three-quarters of the patients were alive and without disability progression

- 81% were relapse-free

- 68% showed no signs of disease activity, including an absence of relapses, disability worsening, or damage detected on MRI scans

Still, responses to treatment can be highly variable, and not all patients will respond to aHSCT for MS the same way.

Is HSC therapy for MS safe?

The major concern after aHSCT is an increased risk of infections, including serious or life-threatening ones, due to the immune system being wiped out. Other risks include:

- chemotherapy side effects, which include fatigue, loss of appetite, hair loss, bleeding, or bruising

- increased risk of developing certain cancers or other autoimmune disorders

- early menopause and fertility issues

Deaths related to aHSCT are now uncommon. MS stem cell transplant risks are generally highest in people who are older, have greater disability, and with other health conditions.

Stem cell transplant is an emerging area of medical tourism, where patients travel to other countries to access medical care that is not readily available in their home country. However, many clinics offering aHSCT lack adequate expertise to minimize complications.

MS patients considering aHSCT should consult with their medical care team to choose an adequate treatment center and determine which medical professionals will be involved. A list of accredited aHSCT centers in the U.S. is available on the Foundation for Accreditation of Cellular Therapy website.

Ongoing clinical trials of stem cell transplant

Several ongoing studies are evaluating the safety and efficacy of aHSCT for MS compared with MS DMTs.

- BEAT-MS (NCT04047628) is a Phase 3 trial comparing aHSCT against the best available DMT in people with highly active, treatment-resistant MS.

- StarMS (ISRCTN88667898) is evaluating the use of aHSCT as an RRMS therapy versus highly effective DMTs, including Mavenclad (cladribine), Lemtrada (alemtuzumab), Kesimpta (ofatumumab), and Ocrevus (ocrelizumab) in people with highly active RRMS.

- RAM-MS (NCT03477500) is a Phase 3 trial testing aHSCT against Lemtrada, Mavenclad, or Ocrevus in RRMS patients who had significant inflammatory activity in the previous year.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

MSCs have potent immune-modulating properties that tend to promote an anti-inflammatory effect. Preclinical research has suggested that MSC therapies can reduce inflammation and slow disease progression in models of MS.

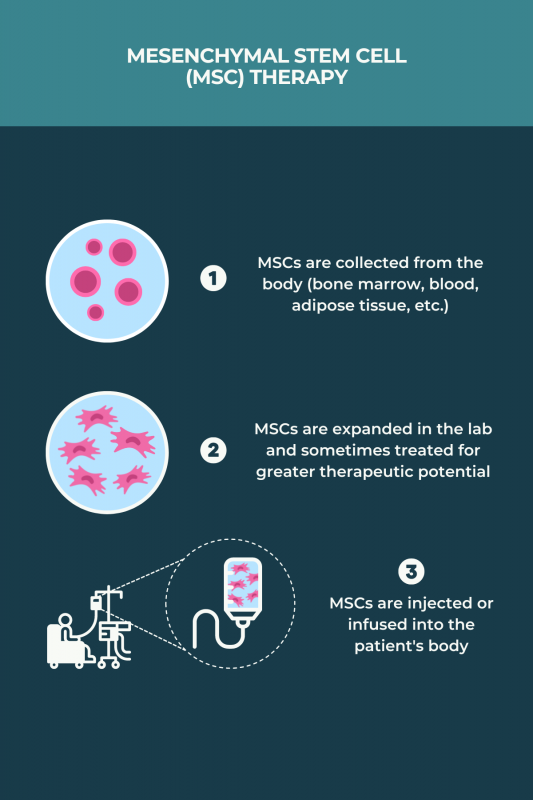

MSC transplants for MS can be allogeneic or autologous. Unlike aHSCT, they do not require chemotherapy. The procedure generally involves:

- collecting MSCs, usually from bone marrow or adipose (fat) tissue, although blood and human umbilical cord sources have been used in some studies

- growing and multiplying the cells in the lab over a few weeks, sometimes treating the MSCs with chemical cues for them to acquire greater immunosuppressive and neuroprotective characteristics

- returning the MSCs to the body via infusion into the bloodstream or an injection into the spinal canal

In contrast to HSCs for MS, MSC transplants are not yet used in clinical practice. This type of therapy is currently only available through MS clinical trials.

How effective is MSC therapy for MS?

Research into the role of MSCs for MS is ongoing, so the effectiveness of this approach for MS remains unclear, including the optimal MS treatment protocol and the patient populations most likely to benefit.

Clinical studies conducted to date have suggested that MSC-based therapies may offer some benefits, including:

- reducing inflammation

- easing disability and MS symptoms

- improving quality of life

Still, these studies have varied widely in terms of treatment protocols and outcomes, so more MSC stem cell research for MS is needed.

Is MSC therapy for MS safe?

Since research on MSC therapies in MS is still in its early stages, the safety profile of these potential treatments remains unclear. However, these treatments do not compromise a person’s immune system like aHSCT does, and most studies to date have not reported any serious safety concerns related to MSC therapies.

Side effects reported in some studies include:

- infusion-site reactions

- fatigue

- nausea

- headache

Ongoing clinical trials of MSC therapies

A number of ongoing early-stage clinical trials are testing MSC therapies for MS.

- A Phase 1/2 trial (NCT05532943) is testing the experimental MSC-based therapy UMSC01 in people with RRMS and secondary progressive MS. UMSC01 uses umbilical cord MSCs isolated from healthy donors.

- A Phase 1 trial (NCT05003388) is evaluating another umbilical cord-derived MSC therapy, called AlloRx, in individuals with MS.

Multiple Sclerosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by