#ACTRIMS2021 – Young Brain Fluid (CSF) Rejuvenates Memory in Mice

Written by |

Editor’s note: The Multiple Sclerosis News Today news team is providing in-depth and unparalleled coverage of the virtual ACTRIMS Forum 2021, Feb. 25-27. Go here to see all the latest stories from the conference.

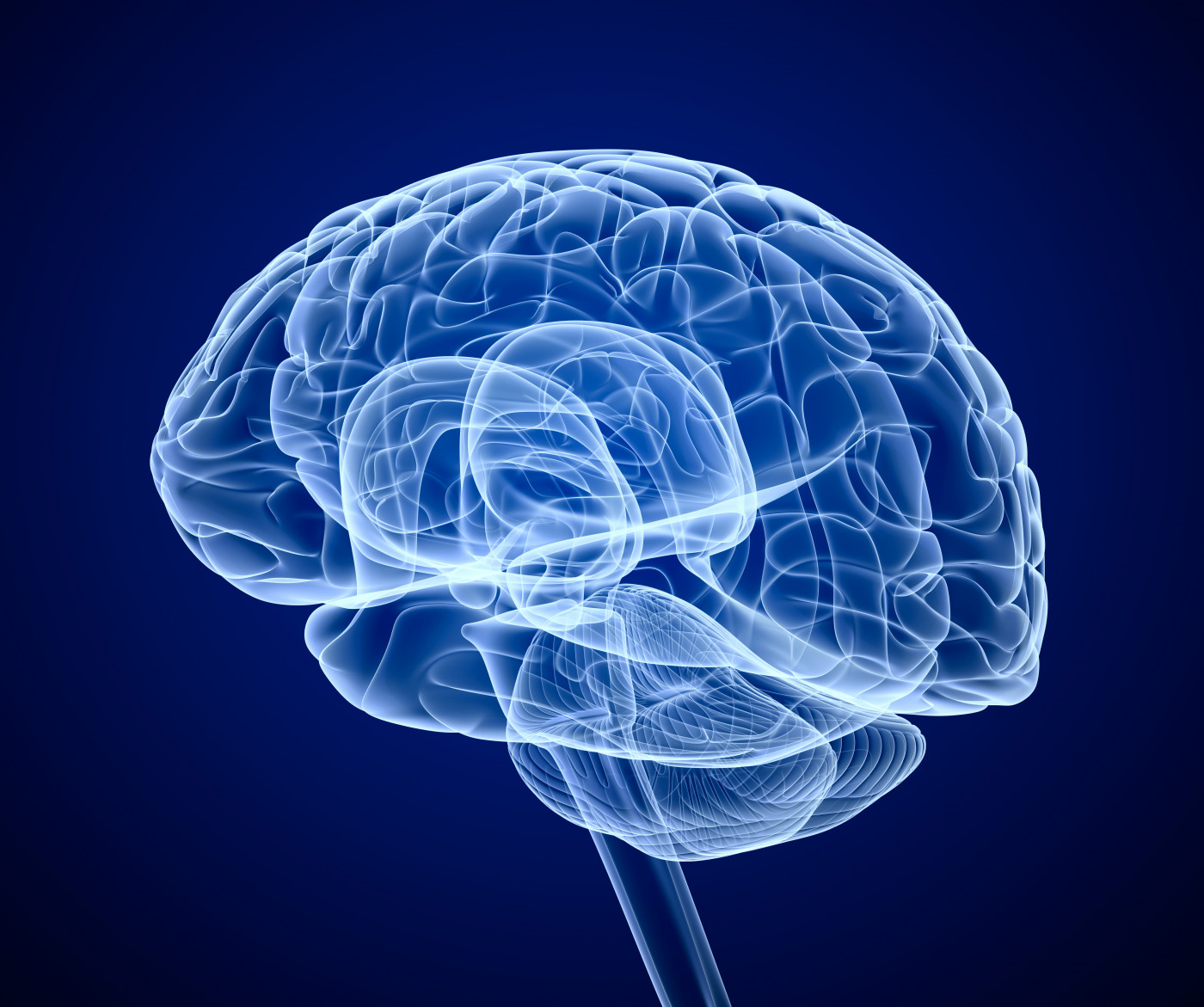

Factors in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounding the brain and spinal cord change with age and can affect memory and the activity of myelin-producing cells, according to experiments in mice.

Now, this new research has found that bathing the brains of aged mice with CSF from young mice had a “rejuvenating” effect on memory — and resulted in more efficient remyelination.

These results may have implications for multiple sclerosis (MS), as MS is characterized by the loss of myelin, the protective coat surrounding nerve fibers.

The findings were shared at the virtual Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Forum 2021, in a presentation titled “Aging and Rejuvenation of Oligodendrocytes,” by Tal Iram, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at Stanford University.

The central nervous system, comprised of the brain and spinal cord, is surrounded by a fluid called the cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF. This fluid is critical for providing brain cells with proper nourishment.

It has been established that the contents of CSF change with age. Specifically, levels of inflammatory molecules tend to increase as people get older, whereas levels of signaling molecules that promote growth decrease. However, the implications of these changes, in terms of brain function and age-related cognitive decline, are not clearly understood.

Furthermore, previous studies using young and aged mice manipulated to share their blood circulation (through a surgical procedure) and specific treatments such as metformin “were shown to rejuvenate OPCs [oligodendrocyte precursor cells] in aging brain and result in more efficient remyelination in aged mouse,” Iram said. Oligodendrocytes are myelin-producing cells.

The team hypothesized that the CSF could carry signals important for oligodendrocyte rejuvenation.

To test this theory, the researchers took CSF from young mice and implanted aged mice with a specialized pump that bathed their brains with the young mice’s CSF. Other aged mice were treated with artificial CSF, as a control group. Conceptually, this experimental design tested whether young CSF applied to an aged brain would have a “rejuvenating” effect.

The results showed that aged mice given this treatment with young CSF performed better on memory tasks — presumably because of alterations in brain function caused by the young CSF, particularly in a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which is important for learning and memory.

Further genetic analyses of the mice’s brains revealed that, after exposure to young CSF, the cell type that responded most was oligodendrocytes. While the main job of oligodendrocytes is to produce myelin, they do have additional functions. Oligodendrocytes are a type of glial cell found in the brain that are not directly involved in sending electrical signals but provide support to the cells that do, which are called neurons.

When the aged mice were treated with young CSF, their oligodendrocytes increased the expression of genes related to their function, including genes associated with the production of myelin.

Based on these findings, “we hypothesized that there might be a factor in CSF that is driving oligodendrogenesis in the aging hippocampus,” Iram said. Oligodendrogenesis is the process by which oligodendrocytes are formed by the growth and differentiation of OPCs.

The researchers then used a compound that labels cells that are actively dividing and tested it in mice’s brains. This experiment revealed more actively growing OPCs in mice that had been given young CSF, compared with those given artificial CSF.

In a separate experiment, mice were treated with young CSF, and their brains were assessed for myelination after three weeks — during which the oligodendrocytes could mature. The results demonstrated that treatment with young CSF led to an increase in the amount of myelin in the hippocampus.

To further confirm these results, the researchers tested the effect of treatment with young CSF or artificial CSF on OPCs in lab dishes (in vitro experiments). Consistent with the results seen in mouse experiments, treatment with young CSF increased cell division of OPCs in vitro, as well as their differentiation — specifically, their growth into mature oligodendrocytes.

“Not only did young CSF drove these cells to a more mature morphology, but also it increased the viability of these cells throughout this process,” Iram said.

Through additional experiments with cells, the researchers teased out part of the molecular mechanism driving these effects. They found that, shortly after treatment with young CSF, OPCs had increased expression of a gene called SRF, or serum response factor.

The protein encoded by this gene, also called SRF, is a transcription factor. That means it helps control whether other genes are “turned on or off.” Specifically, SRF is known to help coordinate cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation.

Additional experiments confirmed that, following young CSF treatment, OPCs had increased levels of genes that are “turned on” by SRF. Changes to the cells’ structure consistent with SRF activation also were observed.

The researchers then looked at the expression of SRF in OPCs in mouse brains. They found significantly higher levels of SRF-expressing OPCs in the hippocampus of young mice, compared with aged mice.

“We believe that SRF might be regulating OPC plasticity in the hippocampus,” Iram said. Plasticity refers to the cells’ ability to change and respond to new stimuli.

Iram and colleagues are currently developing a new mouse model to further study the role of SRF in OPC rejuvenation.