Antigen-loaded Red Blood Cells Help Promote Immune Tolerance in Mice

Written by |

Red blood cells carrying specific antigen proteins on the cell surface can be used to disarm overactive T-cells by promoting immune tolerance, a study in mice found.

The findings may have important implications for the treatment of autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis.

The study, “Persistent antigen exposure via the eryptotic pathway drives terminal T cell dysfunction,” was published in Science Immunology as a collaborative effort between Anokion, a biotechnology company from Switzerland, and the University of Chicago.

Anokion, which focuses on treating autoimmune diseases by restoring immune tolerance, was co-founded by Jeffrey A. Hubbell, PhD, a professor at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago.

“We are excited to publish these data in collaboration with Jeff and the University of Chicago and are proud that our contributions may influence the development of medicines based on driving immune tolerance for patients around the world,” Stephan Kontos, PhD, co-founder and chief scientific officer of Anokion, said in a press release.

“This publication showcases the novel science on which Anokion’s platform is built and underscores the potential therapeutic impact that immune tolerance can have on the treatment of people with autoimmune disorders,” Kontos said.

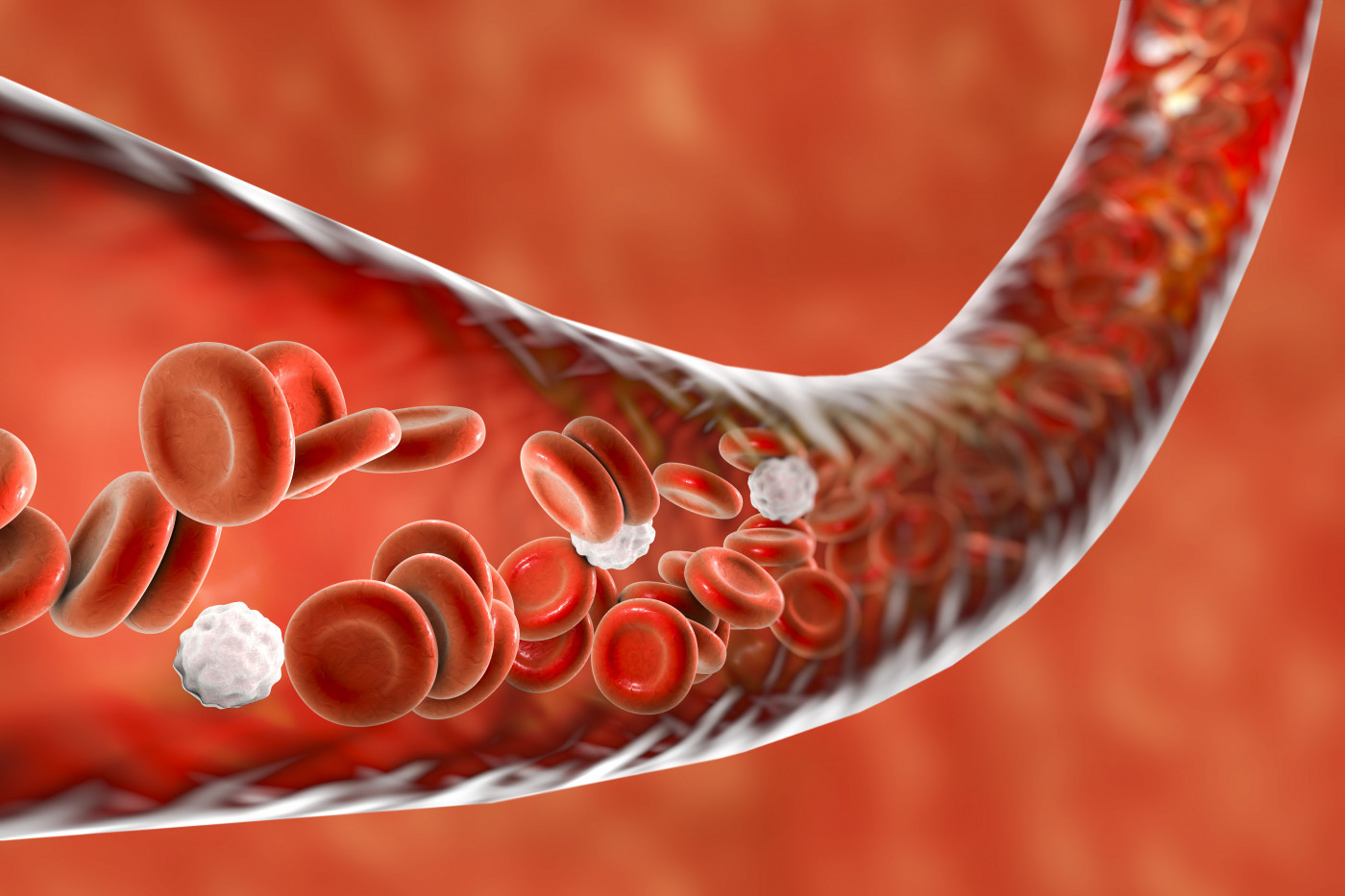

Red blood cells, also called erythrocytes, are cleared from the body’s circulation naturally at a high rate by antigen-presenting cells in the spleen, and so are their cell-surface antigens. Antigen-presenting cells are immune cells that mediate the cellular immune response by presenting antigens — molecules able to trigger an immune response — for recognition by T-cells. T-cells, in turn, are white blood cells that mediate the protection against a potentially threatening antigen.

When T-cells are continuously presented with the same antigen, they stop seeing it as a threat and became unresponsive to it — even months after the removal of the antigen from the bloodstream. This process is known as immune tolerance.

In autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis, the immune system attacks and damages the body’s own tissues and cells (self-antigens). T-cells are involved in the immune responses directed against self-antigens.

Researchers, therefore, hypothesized a strategy they hoped would leave T-cells unresponsive to self-antigens. First, the team identified a human antibody fragment that could bind only to circulating red blood cells. That would allow the antigen proteins to travel to the spleen, where antigen-presenting cells clear red blood cells that are old or damaged.

Then, the scientists analyzed what happened when they injected the antigen proteins in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a widely used model for studies of multiple sclerosis.

Continued exposure to the antigen proteins educated the animals’ immune systems to recognize them as self-antigens. This process induced immune tolerance in T-cells while leaving the rest of the immune system intact. It also prevented mice from showing symptoms of the disease.

“Erythrocyte-targeted antigen prevented … T-cells from contributing to autoimmune pathology, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of leveraging erythrocyte clearance pathways to disarm overactive T-cells,” the researchers wrote.

Anokion has plans to apply this strategy in the clinical development of therapies for multiple sclerosis and celiac disease, two autoimmune diseases.

“Our erythrocyte-targeting technology informed the basis of our novel liver-targeting approach, which we are applying for the development of our pipeline, including our two clinical programs, KAN-101 for celiac disease and ANK-700 for multiple sclerosis,” Kontos said.

According to Hubbell, who serves as Anokion’s chief scientific advisor, the team’s research “could have broad implications on the future discovery and study of treatments” for people with MS and other autoimmune diseases.

“These findings provide important insights into the field of immune tolerance, on both the cellular and subcellular level, unveiling specific details on the molecular pathways within T cells that can drive antigen-specific immune tolerance,” Hubbell concluded.