aHSCT, Stem Cell Therapy for RRMS, Troubled by Unknowns, Paper Says

Written by |

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) has shown some promise as a treatment option for highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), but more clinical evidence is needed to support its use, a team of researchers in the U.K. suggest.

“Uncertainty remains as to how aHSCT compares with current standard of care in patients with highly active RRMS,” the team wrote.

The article, “Is stem cell transplantation safe and effective in multiple sclerosis?,” was published in The BMJ.

While autologous stem cell transplant is not approved in Europe or the U.S. to treat multiple sclerosis (MS), it is sometimes used in RRMS patients with very active disease who have not responded well to other disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).

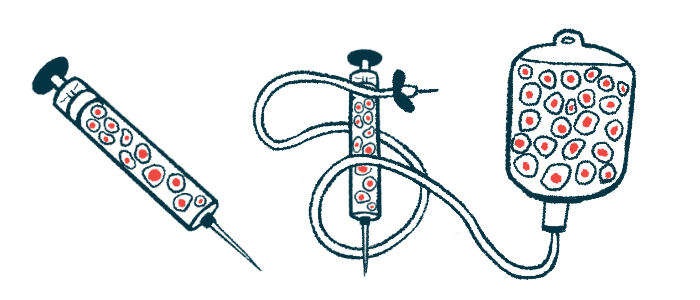

Briefly, the treatment involves collecting stem cells from a patient’s own bone marrow or blood. Then the person’s immune system is partly or completely ablated with a course of aggressive chemotherapy in an effort to reset the aberrant autoimmune responses characteristic of the disease. The collected stem cells are then returned to the patient via an infusion, where they are intended to reactivate the immune system and return it to a functional state.

Current evidence suggests that this procedure can slow disease progression in people with highly active RRMS. However, given the potential risks and the lack of adequate clinical trials comparing stem cell transplant with newer and higher efficacy DMTs, the procedure remains controversial.

A research team at Sheffield and Cambridge institutions discussed what is known about aHSCT therapy and what remains uncertain about its use.

To date, only two randomized clinical trials have compared the use of aHSCT against approved DMTs in MS patients, the scientists noted. A Phase 2 randomized trial in 21 patients showed evidence that aHSCT lowered disease activity on MRI scans compared with mitoxantrone, but it did not delay disability progression.

A larger trial (NCT00273364) involving 110 patients with highly active disease despite DMT use showed, at a median of two years of follow-up, a slowing of disability progression among aHSCT-treated patients compared with those using standard treatments. However, that study did not include the use of newer DMTs, which are more effective than older ones, the researchers noted.

Recent reviews with data from single-treatment clinical trials and observational studies also report a general reduction in disease activity with aHSCT — between 61% and 92% of patients experienced no relapses, disability worsening, or new lesions, a status called no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) after two years of follow-up.

But the lack of a control group for comparison in these studies prevent firm conclusions from being drawn, the team said.

Safety remains an ongoing concern that adds to the uncertainty surrounding aHSCT. Transplant-related complications, such as anemia, a deficiency in immune cells able to fight infections, low platelet counts, fever, and diarrhea are known to occur with aHSCT.

Data, however, suggest that the rates of treatment-related mortality are declining over time. One meta-analysis of 15 studies showed an overall treatment-related mortality rate of 3.6% (15 deaths among 415 patients) in studies conducted prior to 2005, compared with 0.3% (1 in 349 patients) in those conducted between 2005 and 2016.

A separate data review by The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation noted a treatment-related mortality rate of 0.7% between 2008 and 2016.

As aHSCT therapy can be performed at varying intensities, a direct comparison of safety profiles is needed, the scientists noted.

“No evidence suggests that high intensity regimens confer a long term therapeutic benefit, but toxicity and [treatment-related mortality] are likely to be greater. Expert consensus is for the use of an intermediate regimen,” the researchers wrote.

Few data exist on the relative cost-effectiveness of stem cell therapy compared with DMTs. Since aHCST is performed once and thought to have long-lasting effects, it has been suggested that it may offer savings in the long run, but evidence is “not conclusive,” the team noted.

In a March interview story for Multiple Sclerosis News Today, a woman with RRMS who underwent the procedure in 2017 said her aHSCT regimen cost about $125,000.

Multiple trials directly comparing aHSCT with DMTs in RRMS patients are now ongoing or planned. One such trial, called StarMS (ISRCTN88667898), is evaluating aHSCT’s safety and efficacy against DMTs considered “highly effective”: Ocrevus (ocrelizumab), Lemtrada (alemtuzumab), and, possibly, Mavenclad (cladribine). This trial is recruiting people with highly active RRMS, ages 16 to 55, at sites in the U.K.; those interested need to complete an online eligibility questionnaire.

These studies could provide needed clinical, imaging, and safety data on aHCST, the researchers noted.

“A plan is in place to harmonise long term data collection across these trials to provide an opportunity to analyse a larger combined dataset for efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness of this treatment,” the researchers wrote.

Meanwhile, “we suggest that patients being considered for aHSCT should be treated as part of a clinical trial or included in a registry study,” the team concluded. “To minimise adverse events, potential patients require a thorough evaluation of fitness and an assessment for risk factors. They must be informed of the potential risks of treatment and uncertain benefits.”