Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS), an inflammatory central nervous system disease that affects the brain and spinal cord, can be divided into several types based on how symptoms manifest and progress over time. Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) is an advanced stage of the disorder in which neurological symptoms gradually worsen over time.

What is secondary progressive MS?

In all types of MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks myelin, the protective coating surrounding nerve cells, leading to nerve cell damage and dysfunction in the brain and spinal cord.

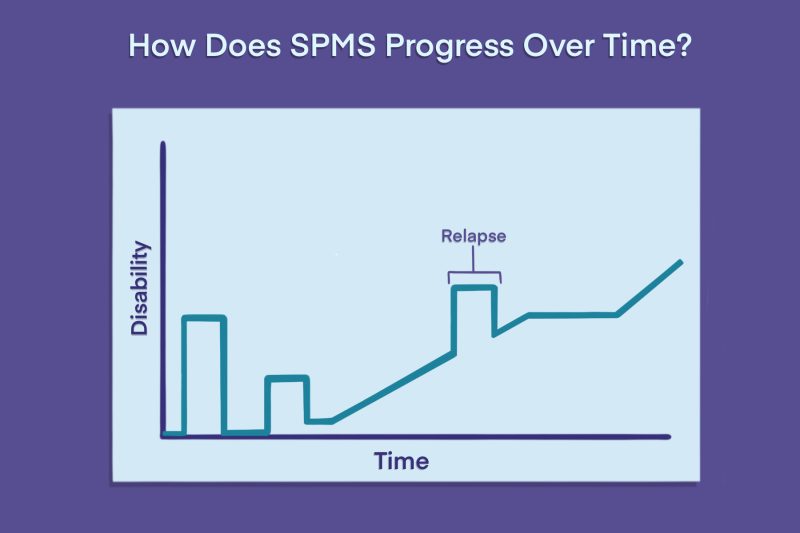

Most MS patients are initially diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), a form of the disease characterized by periods of sudden symptom worsening, or relapses, interspersed with periods of recovery, or remission, where symptoms ease and stabilize.

Over time, some people with RRMS transition to SPMS, where symptoms worsen even without relapses. Some SPMS patients still experience relapses, but symptoms do not completely go away after the relapse and will continue to get worse after the attack.

Physicians also classify SPMS in a couple of other ways:

- Active SPMS vs. nonactive SPMS: Relapses or new areas of damage (lesions) visible on MRI scans are evident in active SPMS, but not in nonactive SPMS.

- With progression vs. without progression: SPMS is characterized as with progression if disability is actively worsening, or without progression when disability is stabilized.

Symptoms of SPMS

As with other MS types, SPMS symptoms can vary markedly between patients, depending on which parts of the brain and spinal cord are most affected in each individual.

People with SPMS are generally more likely than those with RRMS to experience difficulty walking and coordination problems. As progressive MS disability accumulates over time, these problems can get worse and have an increasing impact on daily life.

Other common symptoms in SPMS, many of which overlap with other MS types, include:

- fatigue

- unusual sensations like numbness or tingling, referred to as dysesthesias

- vision problems

- muscle spasticity or stiffness

- bladder or bowel problems

- sexual difficulties

- cognitive challenges

- emotional difficulties

Onset: Transitioning from RRMS to SPMS

Historically, almost all people with relapsing-remitting disease have developed the secondary progressive type, although exactly what causes the RRMS to SPMS transition is not completely understood.

The mechanisms of disease progression seem to differ between the two disease stages. While inflammation and nerve damage are always evident, their relative contributions may change over the disease course.

- RRMS symptoms are thought to be driven by active inflammation, which is why patients with this type usually show more new lesions or lesions with active inflammation on MRI scans.

- SPMS is thought to be largely driven by the progressive loss of damaged nerve cells, which is why these patients tend to have more inactive or chronic active lesions, also known as smoldering lesions, on MRI scans.

Chronic active lesions in MS may represent areas of slow, incremental damage over time.

The timing of an RRMS to SPMS transition varies, and not everyone with RRMS will develop SPMS. Estimates have indicated that, left untreated, about 90% of relapsing-remitting patients develop SPMS within 25 years of an RRMS diagnosis.

Now, however, most RRMS patients receive disease-modifying treatments that can slow MS progression, potentially delaying or preventing the development of SPMS. Newer estimates suggest that 10% of treated patients convert over a median of approximately 30 years.

Factors that have been associated with a faster onset of SPMS include:

- older age at MS onset

- being male

- experiencing many relapses, or rapidly worsening disability, early on in the disease course

- a longer disease duration

- having greater numbers of lesions

- having spinal cord involvement

- having smaller brain volume

- geographical location

Diagnosis of SPMS

There are no formal diagnostic criteria that define when RRMS transitions to a progressive stage. Instead, SPMS diagnosis requires a careful review of symptoms and progression in the preceding months and years. Diagnostic uncertainty is common during this transition, and establishing a diagnosis of SPMS can take years.

Generally, a transition to SPMS may be considered if neurological symptoms have progressed for three to 12 months independent of relapses. However, each physician may have different criteria; for example, some doctors will only diagnose SPMS if the patient has reached a certain magnitude of disability.

Doctors may use a variety of MS neurological assessments and tools to track changes in disease activity over time. These include:

- the Expanded Disability Status Scale, a standardized rating system to measure disability

- other functional assessments of motor ability, upper limb function, and dexterity

- neuropsychological tests to assess cognitive changes

- MRI scans to look for new disease and active lesions

- a lumbar puncture, or spinal tap, to look for signs of MS-related inflammation in the spinal fluid

In very rare cases, individuals may receive an SPMS diagnosis without ever having had an RRMS diagnosis. This can occur if there is clinical evidence of RRMS that wasn’t recognized at the time, and the patient had already transitioned to SPMS by the time of diagnosis.

Treatment of SPMS

SPMS treatment generally involves a combination of therapies that target underlying disease processes to slow MS progression, medications to control severe relapses, and supportive approaches to ease symptoms and improve quality of life.

Disease-modifying therapies

Several disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for SPMS are available. While they don’t cure MS, these treatments can reduce the frequency of relapses and delay disability progression.

Most available DMTs are approved in the U.S. for relapsing forms of MS, which include clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), RRMS, and active SPMS. Approved DMTs include:

- Aubagio (teriflunomide)

- Avonex (interferon beta-1a)

- Bafiertam (monomethyl fumarate)

- Betaseron (interferon beta-1b)

- Briumvi (ublituximab-xiiy)

- Copaxone (glatiramer acetate injection)

- Extavia (interferon beta-1b)

- Gilenya (fingolimod)

- Kesimpta (ofatumumab)

- Lemtrada (alemtuzumab)

- Mavenclad (cladribine)

- Mayzent (siponimod)

- mitoxantrone

- Ocrevus (ocrelizumab)

- Ocrevus Zunovo (ocrelizumab and hyaluronidase-ocsq)

- Plegridy (peginterferon beta-1a)

- Ponvory (ponesimod)

- Rebif (interferon beta-1a)

- Tascenso ODT (fingolimod)

- Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate)

- Tyruko (natalizumab-sztn)

- Tysabri (natalizumab)

- Vumerity (diroximel fumarate)

- Zeposia (ozanimod)

In Europe and elsewhere, some of these therapies are approved only for RRMS, and not active SPMS or CIS.

Mitoxantrone is the only one of these DMTs that is approved in the U.S. for nonactive SPMS.

Treating relapses

Compared with RRMS relapses, flare-ups in SPMS tend to be less frequent and severe. Still, people with SPMS sometimes experience severe relapses that cause significant disability or require hospitalization.

In those cases, anti-inflammatory medications may help ease symptoms and resolve the exacerbation more quickly. These treatments include:

- glucocorticoids, more commonly known as steroids

- adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-based therapies

- plasma exchange, known as plasmapheresis

Symptom management

Several other therapies and interventions can help manage specific MS symptoms. For example:

- Muscle spasticity in MS may ease with oral or injected muscle relaxants.

- MS fatigue management relies largely on lifestyle changes, like reducing stress and exercising.

- Movement problems may be managed with mobility aids, medications such as Ampyra (dalfampridine), or the Portable Neuromodulation Stimulator, known as a PoNS device.

- Bladder, bowel, and sexual problems can be treated with physical therapy, lifestyle changes, or medications.

- Mental health and mood challenges can be addressed with talk therapy and/or medication.

Outlook of SPMS

SPMS prognosis varies substantially between individuals. While the disease isn’t fatal itself, MS-related disability can increase the risk of life-threatening complications.

Other factors can also influence the outlook for patients, including whether an individual experiences relapses and, if so, how frequently they occur. Generally, a faster progression from RRMS to SPMS is associated with a poorer long-term prognosis.

Specific research on life expectancy in SPMS is inconclusive, but people with MS generally live an average of five to 10 years less than their peers. With the availability of modern treatments, this gap is continuing to close.

Once the transition to SPMS is confirmed, patients and their healthcare providers should discuss whether it makes sense to adjust the care plan to help manage the new disease course. This may involve switching DMTs, making lifestyle adjustments like quitting smoking and adhering to a healthy diet, and physical or occupational therapy to make managing symptoms easier in daily life.

Multiple Sclerosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by