Boosting Cellular Energy at Sites of Myelin Loss May Stop MS Progression

Written by |

Loss of myelin in nerve cell fibers — the hallmark of multiple sclerosis (MS) — leads to a shortage of mitochondria, a cell’s powerhouse, denying these damaged fibers the energy they need to work as intended, a new study shows.

Boosting the migration of mitochondria to affected nerve fibers, supplying them with needed energy, may help to protect nerves from degeneration and halt disease progression. Indeed, it may offer a new way of treating progressive MS.

The study “Enhanced axonal response of mitochondria to demyelination offers neuroprotection: implications for multiple sclerosis” was published in the journal Acta Neuropathologica.

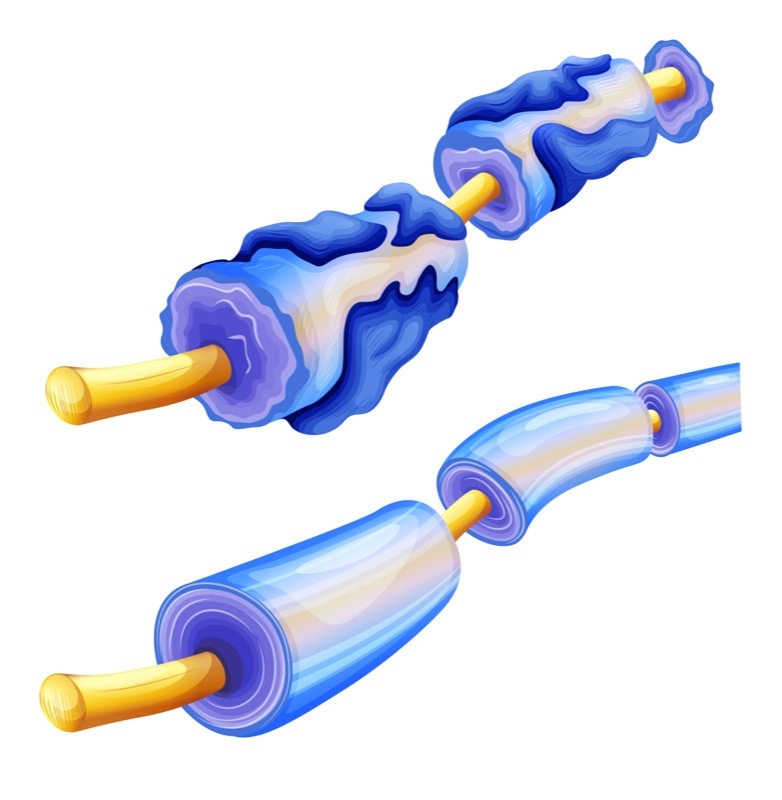

MS is caused by the destruction of myelin, the fat-rich substance that wraps around and insulates nerve cell fibers (axons). Axons are projections of nerve cells that conduct the electric impulses that allow these cells to communicate.

To work as intended, damaged axons require large amounts of energy, which is provided by mitochondria. To compensate for the resulting energy imbalance, neurons respond by increasing their mitochondrial content. Mitochondria are small cellular organelles that work as the cell’s power plant: they produce energy molecules such as ATP, the most common cellular energy source.

However, in nerve cells of MS patients, mitochondria function is often affected. Evidence suggests people with progressive MS have genetic alterations that impair energy production.

A team led by researchers at the University of Edinburgh investigated whether targeting mitochondria in neurons could help mitigate the loss of myelin (demyelination). The study was supported by the National MS Society.

Researchers hypothesized that neurons would respond to demyelination by moving mitochondria from the neuron’s body to the damaged axon.

Real-time imaging of fluorescent mitochondria showed that in healthy neurons in mice — namely, in Purkinje neurons (found in the cerebellum, the center for motor coordination) and sensory dorsal root ganglia (DGR) neurons — mitochondria migrated into the region of the axon where demyelination was present. They named this process “axonal response of mitochondria to demyelination” or ARMD.

ARMD peaked at five days post-demyelination in the cerebellum neurons, and by day seven in the DGR neurons, showing that axons are vulnerable for a few days after myelin is destroyed, and the therapeutic window to target this response process is short.

Next, researchers evaluated several ways of enhancing mitochondrial numbers and migration. One was by boosting the levels of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1-alpha), a key protein involved in mitochondria production. This boost led to an increase in the content and transport of mitochondria to axons, mimicking the ARMD process.

Based on this result, researchers tested pioglitazone, a type 2 diabetes medicine (sold as Actos, among other brand names) known to boost the PGC1-alpha pathway. The treatment was seen to recreate previous findings, with the therapy enhancing mitochondria transport to the axons.

“Taken together, these findings indicate the potential of targeting mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis in neurons to enhance ARMD,” researchers wrote.

Since mitochondria function is deficient in progressive MS, namely in the complex IV (a key component for the production of energy), researchers evaluated whether ARMD could still be neuroprotective for neurons lacking sufficient complex IV.

They observed that in six out of 18 progressive MS cases analyzed, a positive correlation existed between complex IV deficient neurons and mitochondria content, area, and number. This supported the idea that, despite complex IV deficiency, neurons affected by MS still respond to demyelination by mobilizing mitochondria to their axons.

Researchers then developed a mouse model deficient for the complex IV (called COX10Adv mutant mice), and tested pioglitazone.

The treatment was given in the animal’s diet for six weeks. Results showed that mitochondrial content in axons increased significantly, and protected neurons from demyelinating lesions.

Researchers also observed that pioglitazone not only provided protection to myelin loss, but also helped to maintain synaptic function, meaning the neurons remained capable of transmitting signals.

“Our findings clearly illustrate a key compensatory role for mitochondria as part of the neuronal response to demyelination,” the researchers wrote. “Increased mobilisation of mitochondria from the neuronal cell body to the axon is a novel neuroprotective strategy for the vulnerable, acutely demyelinated axon.”

Overall, these findings support the potential neuroprotective benefits of therapies that enhance ARMD for diseases like MS.

“We propose that promoting ARMD is likely to be a crucial preceding step for implementing potential regenerative strategies for demyelinating disorders,” the team added.

In addition to the National MS Society, this research project was funded by the MS Society of the United Kingdom, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and a Challenge Award from the International Progressive MS Alliance.