Brain Structures Tied to Worse Memory in Pediatric-onset MS

Written by |

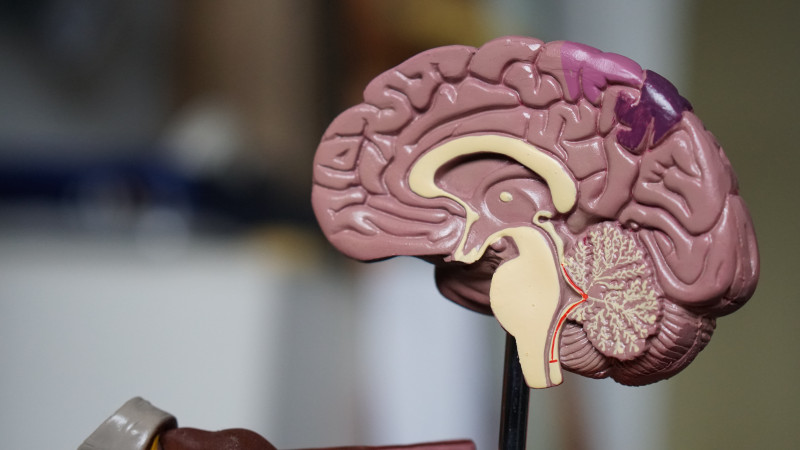

Robina Weermeijer/Unsplash

People who develop multiple sclerosis (MS) in childhood have more difficulty recognizing words and faces than healthy individuals, a small study found.

The volume of certain structures of the limbic system — a part of the brain involved in memory and emotion — is smaller in those with MS, and this loss of volume now has been linked to poorer long-term memory.

The study, “Memory, processing of emotional stimuli, and volume of limbic structures in pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis,” was published in the journal NeuroImage: Clinical.

MS is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by damage to the myelin sheath, a coating that protects nerve projections and helps them send signals more efficiently. The loss of myelin affects various processes in the brain, and children and adolescents with MS are thought to be particularly vulnerable to symptoms such as impaired cognition.

A team of researchers in the U.S. and Canada set out to investigate if people with pediatric-onset MS (POMS) have more trouble remembering words or faces, or recognizing emotions, than healthy people of the same age.

They also sought to understand whether certain structures of the limbic system — such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus — could be involved in impaired cognition.

The study included 65 patients with POMS, with an average of 18.3 years, whose data was collected at the Canadian Pediatric Demyelinating Study. Their mean disease duration was 3.8 years, and almost three-quarters were female. A group of 76 age- and sex-matched healthy individuals served as controls.

All patients completed the Penn Computerized Neurocognitive Battery, a test that measures accuracy and speed on certain tasks. The researchers focused on episodic memory (a type of long-term memory that involves recollection of previous experiences) and identification of emotions.

Results showed that POMS patients performed worse than controls at tasks related to episodic memory, but not on those related to emotion identification. More specifically, patients were less accurate than controls on a test requiring immediate recognition of words, and also slower at recognizing faces that had been presented recently.

Of note, excluding three controls with high emotional distress did not meaningfully alter the results, the researchers noted. These controls, therefore, were retained in all subsequent analyses.

Due to the loss of myelin and resulting neurodegeneration, MS patients tend to experience a reduction in overall brain volume and in the volume of specific regions of the brain. In this study, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans revealed that the volume of the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus was significantly smaller in patients with POMS than in controls.

This smaller volume was associated significantly with worse performance on the memory tests. In particular, the researchers found that both the volume of the hippocampus and of the thalamus could predict accuracy in the word memory test.

Despite a loss of volume of the amygdala — a brain structure involved in emotion and reasoning —emotion identification was not affected in patients with POMS.

“The present study provides evidence showing that patients with POMS may experience deficits in episodic memory and in their ability to recognize faces quickly,” the researchers concluded. “Reduced volume of the thalamus and hippocampus may contribute to some observed deficits in episodic memory.”